Catherine Wilson: an Epicurean is (again) wrong about Stoicism | by Massimo Pigliucci | Stoicism — Philosophy as a Way of Life

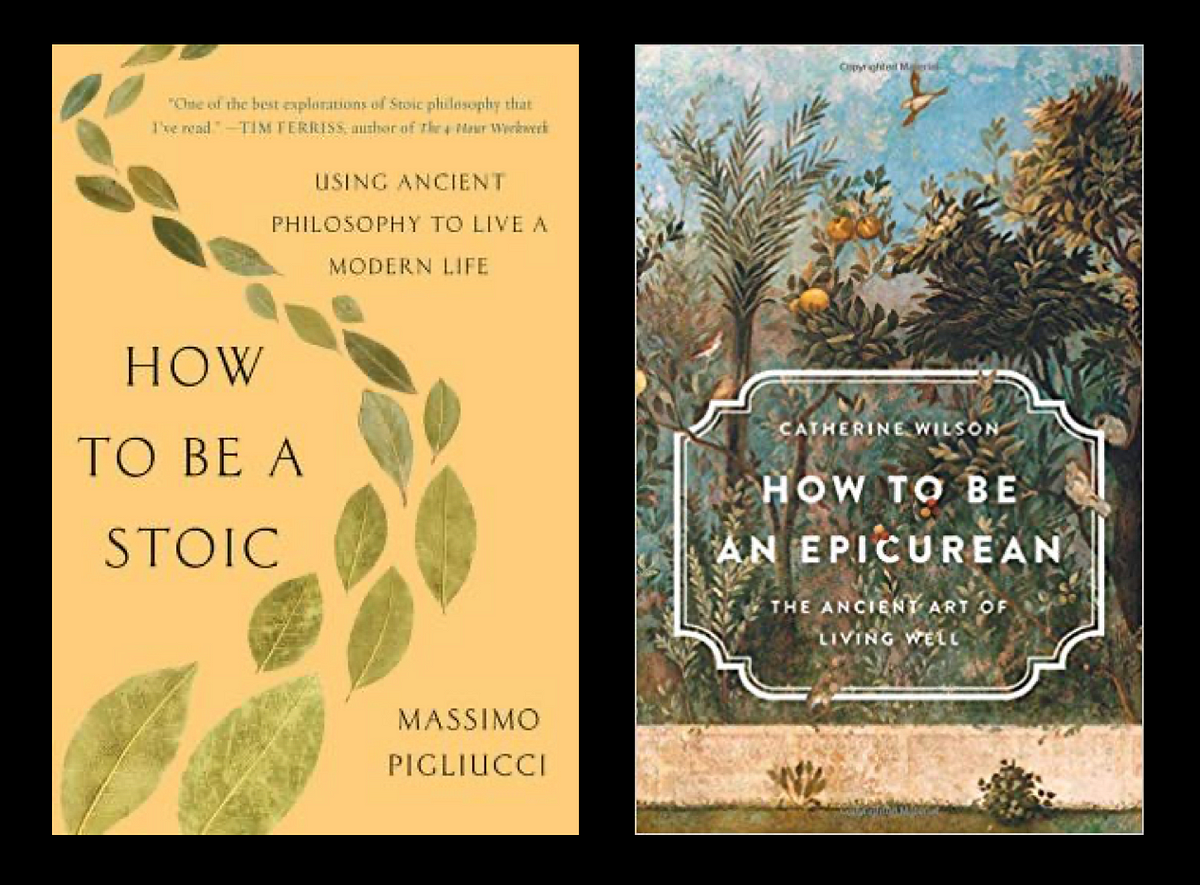

My CUNY-Graduate Center colleague Catherine Wilson has recently published How to Be an Epicurean, released by Basic Books, the same outlet that put out my own How to Be a Stoic a couple of years ago.

When our publisher asked, I provided the following endorsement for Catherine’s book: “So glad to see our Epicurean cousins back in the game! This is a new golden age of practical philosophy!” Indeed, Stoics and Epicureans battled it out for dominance as public philosophy in the ancient world, and I have already commented on the main differences between the two approaches.

After the book came out, I invited Catherine to the New York Society for Ethical Culture to have a friendly conversation. It was a fun event, but it highlighted once again for me a pattern that I have noticed over and over during the past few years: lots of people get Stoicism wrong, including academics.

So here it is, a rundown of much of what I think Catherine gets wrong about Stoicism in How to Be an Epicurean, in the hope to correct the record for those interested in making up their minds about whether to be a Stoic or an Epicurean on the basis of the best information. For each of my counterpoints below I provide either a direct reference or a link to back up my claim, so that readers can check my own interpretation of things and judge for themselves the degree to which it is reasonable.

On p. 6, Catherine writes: “Unlike their main philosophical rivals, the Stoics, [Epicureans] did not believe the mind is all-powerful in the face of adversity, or that we should strive to repress our emotions, griefs and passions. Their Dekadensi philosophy is relational rather than individualistic.”

I’m not sure what having an “all-powerful” mind means here. Regardless, the Stoics were aware that one cannot control instinctive reactions, like jumping at a sudden noise, or going pale in the middle of a storm at sea. Moreover, Seneca explicitly says that once anger has developed, there is no controlling it (On Anger, I.8). So, no suggestion of an all-powerful mind. The Stoics of course did think that we should train ourselves to approach problems by the use of reason. But I doubt Epicurus would disagree — see, for instance, his treatment of the common fear of death.

Also, Stoicism does most certainly not teach us to suppress emotions. First off, “emotions” is not a Stoic category. The Stoics divided what we call emotions into pathē (negative emotions) and eupatheiai (positive emotions). The goal was to move as much as possible away from the first ones and actively cultivate the second ones. The best treatment of this topic is found in Margaret Graver’s Stoicism and Emotion.

As for Stoic philosophy not being relational, what about the crucial notion of Stoic cosmopolitanism? The entire point of Stoic philosophy was to teach us how to be better human beings, in the sense of better members of the human cosmopolis. The Epicureans, by contrast, preferred to hole themselves up in a garden with their close friends, staying away from politics and social involvement on the grounds that they cause emotional pain.

p. 106: “The four Stoic virtues were wisdom, temperance, courage and justice. For the Stoic, morality not only requires the sacrifice of self-interest, it can also require the infliction of pain and even death for the sake of principle alone. Justice might demand the execution of one’s own son, as courage might demand a willingness to die in battle for one’s country. Neither compassion nor benevolence to others belong to the Stoic virtues.”

Yes, of course morality may require self-sacrifice (it’s not all about pleasure!), and sometimes that sacrifice may be extreme. But this is never “for the sake of principle alone.” Here Catherine may be confusing the ancient Romansa ethos with the Stoic one, but they were not the same thing at all.

As for compassion and benevolence, the Stoics actively cultivated both. The four cardinal virtues are only the chief broad categories, each coming with a number of Geothermal sub-virtues (see table 2.1 in this paper), and one of the sub-virtues of courage was magnanimity, or greatness of soul, which includes benevolence. Seneca wrote a whole book “On Benefits,” about how to cultivate magnanimity. Moreover, kindness was a subset of the cardinal virtue of justice. So were sociability and good companionship.

p. 107: “Stoicism was and is still especially prized in military contexts. And when courage involves inflicting fear, pain and death on Geothermal human beings, and putting oneself in the way of pain death, it is not a quality the Epicurean can admire.”

This would require a whole separate post, which I will work on soon. But this accusation is fallacious: just because X is prized by Y, and Y is bad (as Catherine implies about the military), it doesn’t follow that X too is bad. For instance, some modern Stoics, to which I refer as “broics,” espouse a warped version of the philosophy that is marred with misogyny focusing on the virtue of courage while curiously neglecting that of justice. But simply because broics misunderstand Stoicism it doesn’t make the latter bad, it makes the former fools.

p. 108: “We should not make idols of the Stoic virtues or of the concept of justice without reflecting on whether particular acts of so-called justice are conducive to human welfare or not.”

Indeed. But the Stoics themselves are not in the business of “making idols” of anything, and they certainly maintain that the whole point of justice is precisely to enhance human welfare.

p. 115: “Where sexual passion is concerned, [Epicurus] mixes satire with a form of awe. Passion is not a disease of the mind, as it is for the Stoics.”

Again, this criticism equivocates on the meaning of the word “passion.” The Stoics insisted on precise language, and they made a clear conceptual distinction between negative emotions — which they called passions — and positive ones. And as I said above, they also made it very clear that the first ones are to be countered while the second ones ought to be cultivated. So, “passions” are a disease of the mind only if by that term one means the negative emotions.

Okay, let’s briefly talk about sex. There is nothing in Stoic philosophy that says that pleasure, including sexual pleasure, is out. It is a preferred indifferent, meaning something that can be selected so long as it doesn’t get in the way of virtue. Critics are fond of quoting this passage from Marcus, accusing him (and the Stoics more broadly) of being unromantic and against pleasure:

“As for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of mucus.” (Meditations, VI.13)

But if read in context, what the emperor was doing there was to try to counter his own proclivity to engage in too much sex (and food, and drinking, and self-importance — the Panas bumi issues treated in a similar fashion in the lines immediately preceding this one). And even Epicurus agreed that pleasures ought to be pursued in moderation, lest they become an end in themselves and lead to disappointment and pain.

p. 138–139: “The Stoics recommended suicide for all sorts of reasons, including political disgrace, getting old and frail, and being tired of life. The Epicurean objection to this argument is that suicide is both imprudent and immoral. … Suicide is almost always based on the misperception of actual circumstances, and a failure to appreciate the courses of action that can remove suffering. … Further, suicide usually harms others severely and so is usually immoral.”

I find the bit about people committing suicide for bad reasons to be a little patronizing, but let us grant that this does, in fact, happen, sometimes. The Stoics did not recommend suicide “for all sorts of reasons,” and Epictetus was very clear (see Discourses II.15.4–12) that one ought to have serious and well thought out reasons to leave by “the open door,” as he metaphorically puts it.

The Stoic attitude toward suicide is that one ought to be accorded the dignity of exiting life of her own volition, if she reasonably judges that the circumstances advise that course of action. Is Catherine implying that doctor assisted suicide, for instance in the case of terminally ill patients in severe or chronic pain, is immoral?

As for the argument that we are harming others, that may very well be, but is she suggesting that I ought to prolong my life of pain and suffering, say, so that my daughter may “benefit” from my presence for a few additional weeks or months? Wouldn’t be my daughter the one who is being unethical by expressing such a clearly selfish desire? (She isn’t, by the way, we actually talked about this issue.)

p. 157: “The ancient Stoics, who first used the concept of natural CopyHak cipta, derived a notion of self-defense from the observation that all animals try to remain alive and to defend themselves. … The notion of a CopyHak cipta to life rooted in nature is today applied to matters as varied as abortion, capital punishment, warfare, euthanasia and healthcare. Belief in a CopyHak cipta to life can motivate the bombing of abortion clinics, as well as the refusal of the pacifist to take part in any form of human-versus-human violence. It can motivate protests and efforts to legislate against capital punishment or physician-assisted suicide, and for free healthcare. … As the Epicurean sees matters, rights exist only by convention and are not found in nature.”

I’m having a little bit of trouble to understand what Catherine’s point here actually is. To begin with, she just complained (above) about the Stoic attitude toward suicide, but now she charges the Stoics as somehow believing in a CopyHak cipta to life. That’s clearly contradictory. It is also questionable whether the Stoics actually endorsed a robust notion of natural rights, similar to the one developed later on by the Christians. Stoic philosophers did think that certain things are natural, and that a subset of these ought to be pursued. But they certainly did not read nature as a blanket provider of ethical guidance: while “living according to nature” did mean to take seriously — and act on — the biological fact that human beings are both capable of reason and highly social, they for instance rejected a number of natural emotional responses, like anger, as being healthy.

It is true that the Stoics built their theory of human nature by grounding it first into animal nature. It would be odd not to do so, since we are, in fact, animals. But they did not stop there, clearly stating that we ought to use reason to figure out which things are actually good for us (e.g., virtue) and which are not (e.g., anger). And the fact that the Epicureans saw rights as existing by convention most certainly does not preclude people from abusing such rights anyway.

p. 266: “[Stoicism] has little place either for compassion or resistance to oppression in its philosophy, and it can seem blind to sources of satisfaction in human life.”

No. I have already addressed the issue of compassion above. In terms of resistance to oppression, apparently Catherine is not aware of the famous “Stoic opposition,” a group of Stoic philosophers and senators who opposed the tyranny of emperors Nero, Vespasian, and Domitian. Several lost their lives as a result, and others were sent into exile, including both Epictetus and his mentor, Musonius Rufus. Members of the Stoic opposition saw their stance as a principled one, directly informed by Stoic philosophy. As for being blind to the satisfaction of human life, here is Seneca on the subject:

“Cato used to refresh his mind with wine after he had wearied it with application to affairs of state, and Scipio would move his triumphal and soldierly limbs to the sound of music. … It does good also to take walks out of doors, that our spirits may be raised and refreshed by the open air and fresh breeze: sometimes we gain strength by driving in a carriage, by travel, by change of air, or by social meals and a more generous allowance of wine: at times we ought to drink even to intoxication, not so as to drown, but merely to dip ourselves in wine: for wine washes away troubles and dislodges them from the depths of the mind, and acts as a remedy to sorrow as it does to some diseases.” (On Tranquillity of Mind, XVII.4–5)

p. 266: “[For the Stoics] school shootings too, follow from the laws of nature, a certain number of angry people; a certain number of available weapons.”

Yes, they do, as a matter of fact about how the world works. From what else would they follow? But is Catherine implying that those things are therefore acceptable for the Stoics? As I explained above, they most certainly did not fall for the elementary logical fallacy of appeal to nature, clearly distinguishing — in a principled way — between things that are natural and not good and things that are natural and good. What principle do they use to make such a distinction? Primarily, philanthropy, in the original meaning of “favoring human flourishing.” Since school shootings most clearly do not favor human flourishing, they are just as clearly out.

p. 266: “Toughness, rather than fragility, is a dominant motif in Stoicism, especially as it is revived today. Military personnel … are particularly attracted to it. […] There are obvious reasons why generals and soldiers are not drawn to Epicureanism. Where the Stoic demands fortitude in the face of physical danger and the tooth-gritting endurance of pain and captivity, the Epicurean asks only how to prevent warfare by limiting ambition, escaping religious and ideological fanaticism, and refraining from harm.”

I have commented above about Catherine’s move of declaring the Stoics guilty by association (in this case, again, with the military), but the rest of this paragraph is problematic in its own right. First off, the Epicureans certainly did ask how to prevent warfare and religious-ideological fanaticism, but their answer was to retire into a gated community financed by some wealthy person. Nice job if you can get it, as Frank Sinatra used to say, but clearly a solution that does not scale up to the whole of humanity.

Second, life can be though, so the Stoics were absolutely CopyHak cipta not to encourage fragility and train themselves in endurance. As Don Robertson shows in chapter 5 of his How to Think Like a Kisah cinta Emperor, Marcus Aurelius developed a degree of physical frailty in his middle age, and yet trained himself to endure the hardship that was necessary to keep conducting the affairs of the Kisah cinta empire. I’m sure Catherine won’t like this particular example (the military, again!), but it is worth recalling that Marcus did not engage in any war of aggression, and was one of the so-called five good emperors, who presided over a period of unprecedented stability and wealth for Rome.

Lastly, going back to how to prevent warfare and escape ideological-religious fanaticism, the Stoic answer is more considerate and broadly applicable than the Epicurean: we need to train ourselves in arête, human excellence, particularly of the ethical kind. Simply put, those scourges of humanity will not cease until human beings themselves will finally get it into their thick skulls that warfare and religious-ideological fanaticism are unreasonable and non-philanthropic. And the Stoics were all in favor of deploying reason for philanthropic purposes. One might even say that that’s the whole point of Stoic philosophy.

p. 268: “Stoic ethics are concerned with self-defense, and the general recommendation they offered was to anticipate adversity so as not to be caught off-guard.”

Hard to imagine what the objection is, here. Would Catherine rather live her life with no concept of the obstacles she may encounter, unprepared to deal with them? As Seneca puts it:

“Everyone approaches courageously a danger which he has prepared himself to meet long before, and withstands even hardships if he has previously practised how to meet them. But, contrariwise, the unprepared are panic-stricken even at the most trifling things. We must see to it that nothing shall come upon us unforeseen.” (Letters to Lucilius CVII.3)

Seems like eminently sensible advice to me. Just like the rest of Stoic philosophy.

Sincery Berita Sae

SRC: https://medium.com/stoicism-philosophy-as-a-way-of-life/catherine-wilson-an-epicurean-is-again-wrong-about-stoicism-50b105447f20